Colin Maltby, Executive Director at Maltby Capital (English Solicitor); Guillermo A. Grüning, Consultant at TheMindCo (Argentine Attorney & English Registered Foreign Lawyer); Cecilia Calello, Associate at Maltby Capital (Argentine Attorney) / 11 September 2024

I. Introduction

The impact and rapid evolution of Artificial Intelligence (“AI”) is undeniable. AI continues to contribute significantly to innovation and productivity across various sectors[i] such as finance[ii], healthcare[iii], energy[iv], education[v], transport[vi], and the creative industries[vii], among others[viii].

AI is not only reshaping industries but also challenging traditional legal approaches to intellectual property law – where humans (and not machines) have been at the fore. This article provides a comparative overview of the past and present state of play in both Argentina and the UK, highlighting some of the challenges AI poses.

II. AI-Generated Content: A New Creature?

There is still no accepted definition of AI.[ix] The Alan Turing Institute defines it as: “the design and study of machines that can perform tasks that would previously have required human (or other biological) brainpower to accomplish. AI is a broad field that incorporates many different aspects of intelligence, such as reasoning, making decisions, learning from mistakes, communicating, solving problems, and moving around the physical world.”[x] In turn machine learning (“ML”) is a technology that allows computers to perform specific tasks intelligently, by learning mostly from examples.[xi] ML uses elements of each of these fields to process data in a way that can detect and learn from patterns, predict future activity, or make decisions.

There are mainly three key branches of ML:[xii]

- Supervised machine learning

- Unsupervised learning

- Reinforcement learning

Deep learning, in turn, employs neural networks with multiple layers—hence the term “deep”— to model intricate patterns within data. [xiii] These networks have input, hidden, and output layers, with activation functions that help learn complex patterns. [xiv] Open AI-funded ChatGPT is a large linguistic model that involves deep learning. [xv] On the other hand, AI-generated content encompasses a wide range of works created by AI systems, including but not limited to text, images, audio, video, and other digital materials. This content arises from algorithms and data models, without direct human authorship.

III. Legal Framework for Copyright in Argentina and the UK

III. a. Evolution of Copyright: Common Law and Civil Law Traditions.

Copyright, or author’s right, is the area of intellectual property law that regulates the rights that creators have over their creative goods and the means to exploit these rights for profit. The history of copyright law is rather complex, and there are fundamental differences between common law copyright (British tradition) and civil law “Droit D’Auteur” or “Author’s right” (Argentinian tradition).

In England, although it is certain that with the invention of printing at the end of the 15th Century, a form of copyright protection began to develop in England[xvi], it was not until the Statute of Anne (1710) that all persons were granted the right to claim ownership of copyright in a work and acquire rights for a fixed term[xvii]. The Statute of Anne was a result of the need to regulate book trade and prevent monopoly, emphasising economic rights and based on the idea that it would encourage and promote progress[xviii]. It was the successor of the 1911 Copyright Act, replaced in 1956 and which eventually evolved into the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act (“CDPA”) in 1988.

The civil law droit d’auteur model, on the contrary, is imbued with the demands of 18th Century revolutionary France, which focused on recognizing the author’s natural right over their intellectual creations, on the basis that it is the expression of the author’s personality[xix]. In contrast to utilitarian theories, natural rights theories justify copyright protection on the basis that it is a natural right that arises when a work reflects the personality of the person who created it: laws do not create the right but simply recognise its existence[xx].

In Argentina, specific legislation was adopted later[xxi]: law N° 7.092 was passed in 1910 and then modified in 1914 by Law N° 9.510. Both laws were finally repealed by the Intellectual Property Regime (Law N° 11.723 on Legal Intellectual Property Regime) of September 30, 1933 (“Argentine IP Law”)[xxii]. This law, as amended, provides for the protection of all scientific, literary, artistic or didactic production regardless of the reproduction procedure. Moreover, it states that “Copyright protection shall cover the expression of ideas, procedures, methods of operation and mathematical concepts but not those ideas, procedures, methods, and concepts themselves”[xxiii] [xxiv].

III. b. Definition and criteria for authorship and originality in the UK and Argentina

III. b. I. UK.

Under the CDPA, work must be original to qualify for copyright protection. According to the traditional UK approach, known as the “skill and labour” test, a work can be protected under copyright without the requirement of “literary” merit or style: originality hinges on the author’s personal skill, judgment, and individual effort ensuring that it is not copied from other works[xxv], modified by the ECJ’s decision in Infopaq[xxvi]. One of the most recent UK legal interpretations of this concept is set out in the case of THJ v Sheridan[xxvii], “what is required is that the author was able to express their creative abilities in the production of the work by making free and creative choices so as to stamp the work created with their personal touch”[xxviii]. Concerning authorship and ownership of copyright, the general rule is that the first owner of copyright is the author being the person who creates it or, in the case of Computer-Generated Works i.e. work generated by computer in circumstances such that there is no human author of the work (“CGW”)[xxix], the person by whom the arrangements necessary for the creation of the work are undertaken.[xxx]

Now, a question arises how the originality test sits with works involving no-human author?[xxxi] In the case Nova Productions[xxxii], which predates Infopaq, the court did not explicitly address questions of originality or the level of skill and effort involved, but did hold that players of a game were not authors of any artistic works in it, even though the appearance of any particular screen depended to some extent on the way the game was being played. [xxxiii]

III. b. II. Argentina.

While the Argentine IP Law does not provide a specific definition of “work” nor outlines the exact criteria for protection of works, Article 1 clarifies that intellectual property law safeguards the author’s expression. Legal scholars and court rulings have established the requirements for a work to be eligible for protection, which includes the requirement for originality: the work must show a certain amount of creativity, a result of the human intellect that allows the author’s personal stamp to be distinguished in it: “Originality is a prerequisite for an intellectual work to merit the protection of the law, it is of the essence of intellectual property and forms its very basis. The work of any genre must be the result of an elaboration of the intellect and its originality lies in containing that creative element that constitutes the essence to make it protectable” [xxxiv].

It is generally agreed that the work that deserves protection is “any original and novel perceptible personal expression of the intelligence, the result of the activity of the spirit, that has individuality, that is complete and unitary, that represents or signifies something that is an integral creation“[xxxv].

As for authorship and ownership, the Argentina IP states in Article 4 that the owner of a work is “a) the author of the work, b) His/her heirs or successors in title; c) Those who, with the author’s permission, translate, recast, adapt, modify or transport the resulting new intellectual work, or d) The natural or legal persons whose employees hired to develop a computer program have produced a computer program in the performance of their work duties unless otherwise stipulated”. However, it does not define who the author of the work is. Again, the concept of “author” has been defined by case law and doctrine and, traditionally, the concept of “Author” has been associated with the human person.[xxxvi]

IV. AI Generated Content Protection in the UK and Argentina

IV. a. Subsistence.

With the development of AI machines are starting to create truly creative works that in some cases are even difficult to distinguish from those created by humans. This has caused a universal debate surrounding whether copyright should subsist on a work created by AI and, if so, whether modern copyright law is sufficient to provide such protection[xxxvii]. The first step in evaluating possible answers is to differentiate those cases where AI systems function as tools of human in the creative process, from scenarios where AI is able to create a work autonomously and without human intervention, and whose development has evolved exponentially in recent years.

The first case does not seem to generate much controversy: similar to what happens when a photographer uses a camera with intelligent software to improve the quality of the photograph, the result of the creative process in a computer-aided work can be attributed to the individual using it, since “machine assistance does not disqualify the human agent from being deemed the author“[xxxviii]. As pointed out by the European Parliament, “where AI is used only as a tool to assist an author in the process of creation, the current IP framework remains applicable”[xxxix].

However, it is the second case that presents the most critical challenges to the current law regime.

Both Argentine and British law stipulate that a work must possess originality to qualify for copyright protection. Therefore, under the current standards for originality in both jurisdictions a work must reflect the author’s personality and bear the author’s personal touch to meet the originality requirement. These considerations seem to allude to a natural human person, as personality traits are hard to find on machines. For this reason, one view is that these works “might not be eligible for copyright protection”[xl]. However, “not providing copyright protection could have a negative impact on the development of Al and innovation in this field as without protection there is a lack of incentive for developers to create, use, and improve the capabilities of Al systems”.[xli]

The answer to this issue could potentially be applying a separate, tailored definition of originality to AI-generated content (“AIGC”). There is no need to reinvent the wheel, as for example, the traditional UK “skill and labour” test might encounter fewer challenges than a creativity-focused approach, as it is generally easier to agree that a machine can “work” than to assert that a machine has a personality. [xlii]

UK provisions on CGW also seem to offer potential solutions to the originality requirement. Concerning this topic, in THJ v Sheridan the court stated that the risk and price charts were original, although the degree of visual creativity was low so that the scope of protection conferred by copyright in the charts was correspondingly narrow[xliii]. This case shows how, when analysing compliance with the requirement of originality in CGWs, the Court refers to the “personal touch” of the person by whom the arrangements necessary for the creation of the work were undertaken. However, it is uncertain whether this analysis could be applicable to AIGC where the output is the result of a random set of algorithms and there is no possibility of tracking the “creative choices” of a human person.

IV. b. Authorship and ownership.

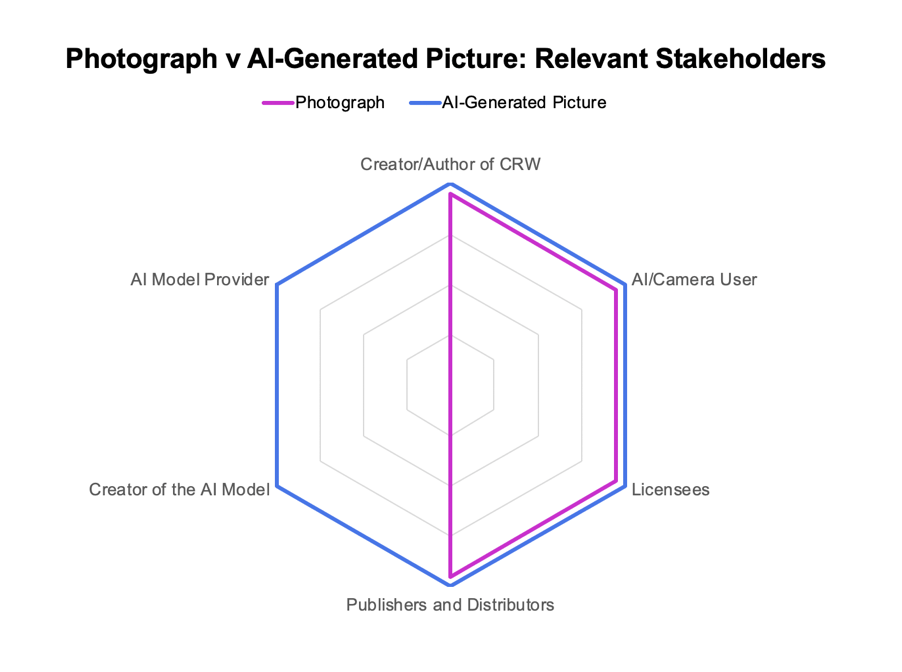

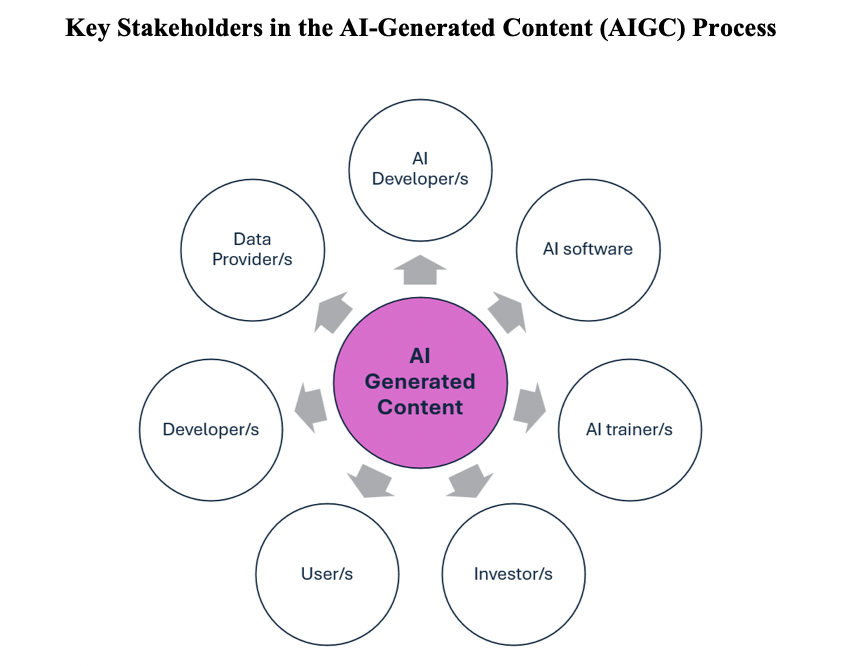

Authorship has over time evolved into a concept with a dual nature: i.e. both a manifestation of personal intellectual effort and a vehicle for economic exploitation. Besides subsistence and originality, a further requirement for works to be copyright-protected is that they originate from one or more authors.[xliv] It is necessary to establish a nexus between the author and a relevant jurisdiction (i.e., a signatory to the Berne Convention) for copyright protection to be granted, and identify the original owner of that CRW.[xlv] However, there is certainly a difficulty when it comes to determining the original owner of a copyright concerning AI-Generated content (AIGC). This process may have had potentially a complex web of interactions with many different stakeholders such as an investor/s, arranger/s/developer/s, AI software, an AI trainer and/or user/s.[xlvi] It is thus key to understand the creation process and the stakeholders involved as well as the extent of input and influence in the final product:

IV. b. I. Approaches to Determining Ownership.

In the absence of a concept of AIGC as such in any of the jurisdictions in question, some of the following positions can be taken.

First, is the proximity approach according to which the individual who is most closely associated with the output should be the original owner. For instance, in the case of LLMs, the user/s would be the closest associated individual at the end of the chain.

Second, the concept of “investment approach” relates to the “corporate governance approach” which prioritise incentivising investment in AI technology development.

Third, there is the work-for-hire approach which is potentially the most pragmatic and predictable approach from a commercial point of view, meaning, the entity commissioning the AI-generated work retains ownership.

Fourth, given the complex and multifaceted nature of the process by which AIGC is created, a “collaborative approach” could require agreements and licensing terms to avoid any conflicts, ensuring that all parties’ contributions are acknowledged and fairly compensated.

Finally, the sui generis approach entails creating a unique category for AI-generated works with specific rules concerning authorship and ownership.[xlvii] While viable, its implementation may require significant legislative changes.[xlviii] Besides statutory dispositions, any concerns about authorship or ownership issues that can somehow affect AIGCs, can be resolved by contract, e.g., T&Cs, licence agreements, and other instruments.[xlix]

IV. b. II. Potential Issues ahead.

It is important to note that in the case of the UK, there is uncertainty about whether AIGC falls firmly within the definition of CGWs. The UK Government has recognised this uncertainty and sought to address it through its consultations on AI and copyright in 2021 and 2022.[l] It ultimately decided not to table immediate changes to the law regarding authorship because the use of AI is still in its infancy.[li]

The dynamics of LLMs may lead to several potential issues, provided that AICGs are considered original and an author can be identified. The complexity of algorithms or opaque data model training techniques are some of the key challenges that may complicate some of the following difficulties. For instance, LLMs like ChatGPT may produce similar or identical outputs for different users, leading to conflicts over ownership.[lii] Thus establishing a clear ownership framework is essential to mitigate such disputes and ensure fair distribution of rights.[liii] Furthermore, misattribution[liv] can give rise to myriad legal and ethical problems.[lv] Also, Generative AI systems which frequently comprise works protected by third-party copyright[lvi] and thus the storage and therefore any output coming from this can contribute to a broad infringement scenario.[lvii]

V. Conclusion

It seems clear that AI has introduced profound challenges to traditional copyright frameworks including the intellectual property law regime. This brought out the pressing need for effective and rapid legislative solutions. This will give room for new AI developments to flourish in both Argentina and the UK through a clear and concise framework of rules for investors, developers and IPRs creators.

VI. References

[i] A recent study, commissioned by the UK Government and published on 29 March 2023, showed that there are more than 3,000 innovative AI companies in the UK, generating more than £10bn in revenues, employing more than 50,000 people in AI-related roles, contributing £3.7 billion in Gross Value Added (GVA) and with a secured £18.8 billion in private investment since 2016. See https://www.gov.uk/government/publications/artificial-intelligence-sector-study-2022/artificial-intelligence-sector-study-2022-ministerial-foreword-and-executive-summary

[ii] See OECD (2023), “Generative artificial intelligence in finance”, OECD Artificial Intelligence Papers, No. 9, OECD Publishing, Paris, https://doi.org/10.1787/ac7149cc-en; and Oliver Wayman (2023) “The AI Revolution in Banking” available at https://www.oliverwyman.com/content/dam/oliver-wyman/v2/publications/2022/sept/ai-revolution-in-banking-report.pdf

[iii] See World Health Organization (2021), “WHO issues first global report on Artificial Intelligence (AI) in health and six guiding principles for its design and use” available at https://www.who.int/news/item/28-06-2021-who-issues-first-global-report-on-ai-in-health-and-six-guiding-principles-for-its-design-and-use

[iv] See World Economic Forum (2021), “Harnessing Artificial Intelligence to Accelerate the Energy Transition” available at https://www.weforum.org/publications/harnessing-artificial-intelligence-to-accelerate-the-energy-transition/ and International Energy Association (2023) “Why AI and energy are the new power couple” available at https://www.iea.org/commentaries/why-ai-and-energy-are-the-new-power-couple

[v] See UNESCO (2023) “Artificial intelligence in education” available at https://www.unesco.org/en/digital-education/artificial-intelligence

[vi] See European Parliamentary Research Service (2019) “Artificial intelligence in transport. Current and future developments, opportunities and challenges” available at https://www.europarl.europa.eu/RegData/etudes/BRIE/2019/635609/EPRS_BRI(2019)635609_EN.pdf

[vii] See Creative Industries Policy and Evidence Centre (2023) “AI and the Creative Industries: The art in the artificial” available at https://pec.ac.uk/research_report_entr/ai-and-the-creative-industries-the-art-in-the-artificial/#:%7E:text=Recent%20breakthroughs%20in%20AI%20could,directly%20analysed%20using%20machine%20learning; European Commission (2022) “Study on Opportunities and Challenges of Artificial Intelligence (AI) Technologies for the Cultural and Creative Sectors” available at https://digital-strategy.ec.europa.eu/en/library/study-opportunities-and-challenges-artificial-intelligence-ai-technologies-cultural-and-creative; and World Economic Forum (2024) “How is AI impacting and shaping the creative industries?” available at https://www.weforum.org/agenda/2024/02/ai-creative-industries-davos/

[viii] In 2022, the UK Government reported that around 15% of all businesses (432,000 companies) had adopted at least one AI technology. See https://www.gov.uk/government/publications/ai-activity-in-uk-businesses/ai-activity-in-uk-businesses-executive-summary

[ix] It is worth noting that within the context of machine learning and AI, a robot typically refers to the embodied form of AI; robots are physical agents that act in the real world. Historically speaking, AI already has its roots back to the 18th Century. In 1763 Thomas Bayes established a mathematical theorem on probability – which became known as Bayes’ Theorem – that remains a central concept in some modern approaches to machine learning. Moreover, Augusta Ada Byron, better known as Ada Lovelace, was also a relevant figure within this field who identified the limits of what computers can do, among many contributions, in a later remark highlighted in one of Alan Turing’s most famous papers as ‘Lady Lovelace’s Objection’. Closer to our era, Turing’s work is widely credited with laying the groundwork for the field of AI as such. It wielded and developed what is known as the Turing Test, a test to determine whether a machine is capable of displaying intelligent behaviour equivalent to that of a human being. Distinctions to scientists such as John McCarthy (US) also deserve to be mentioned. On the other hand, from Argentina’s side, in 1965, the Artificial Intelligence Study Group (GEIA), headed by Horacio Reggino, was created at the Faculty of Engineering. Given the difficulties faced during Onganía’s dictatorship at that time, this task force group was dismantled. See link: https://www.argentina.gob.ar/sites/default/files/manual_-_inteligencia_artificial.pdf Generally, speaking, Argentine scientific research institutions, such as CONICET and the National Academy of Exact, Physical and Natural Sciences, align closely with UK institutions like the Alan Turing Institute and the Royal Society in their AI definitions. However, it is worth noting that the Argentine institutions do not match the exhaustive comprehensiveness of their UK counterparts. For reference, see publications from Argentine institutions such as the following: https://www.ancefn.org.ar/user/FILES/PUBLICACIONES/Desmitificando%20la%20Inteligencia%20Artificial.pdf

[x] The Alan Turing Institute’s website has a glossary with 24 definitions of key terms in data science and artificial intelligence (AI), including algorithmic bias, digital twin, neural network and synthetic data. The Alan Turing Institute, Defining data science and AI, link: https://www.turing.ac.uk/news/data-science-and-ai-glossary

[xi] Machine learning: the power and promise of computers that learn by example, Issued: April 2017 DES4702

ISBN: 978-1-78252-259-1, link: https://royalsociety.org/~/media/policy/projects/machine-learning/publications/machine-learning-report.pdf (“Machine learning has elements such as computer science, statistics, and data science”)

[xii] Ibid.

[xiii] Generative AI models, by their very nature, are huge and resource-intensive. Creating these models requires terabytes of high-quality data, meticulously processed over several weeks using GPU-based high-performance computing clusters. These tasks are only within the reach of a few institutions with the necessary resources and expertise. In addition, these models are computationally intensive to operate and are therefore often available through application programming interfaces (APIs). This allows developers to integrate these models into their existing software ecosystems without the need for additional infrastructure. These generative AI models, aptly named Foundation Models, are remarkably versatile. They can be tailored to a myriad of specific tasks, distinguishing them from single-purpose AI by their ability to perform a wide range of functions. Generative AI is all the rage, Deloitte AI Institute. Link: https://www2.deloitte.com/content/dam/Deloitte/uk/Documents/consultancy/deloitte-uk-us-ai-institute-gen-ai-for-enterprises.pdf

[xiv] Depending on the AI tool developer’s approach, training datasets may consist of free and open information (pure data), protected data (such as copyrighted works) or a mixture of both. Please see IBM, “AI, machine learning and deep learning: What’s the difference?”. Link: https://admin02.prod.blogs.cis.ibm.net/blogs/systems/ai-machine-learning-and-deep-learning-whats-the-difference/

[xv]OpenAI launched ChatGPT in 2022, quickly gaining global attention for its ability to synthesize information and generate captivating and complex content. Large linguistic models (LLMs) like ChatGPT are indeed deep learning technologies using methods like next-token prediction to generate text. Nonetheless, these models do not truly understand meaning; they in fact predict the next word probabilistically, earning the description ‘stochastic parrots’ due to their lack of genuine comprehension. Please see Large Language Models and Intelligence Analysis, Adam C and Richard Carter (The Centre for Emerging Technology and Security, The Alan Turing Institute). Link: https://cetas.turing.ac.uk/publications/large-language-models-and-intelligence-analysis

[xvi] Members of the book trade were given a royal charter and became the Stationers’ Company. After several royal charters, the Licensing Act of 1662 gave the Stationers’ Company powers to seize books, establish printing presses and publish books. See Jane C. Ginsburg, A Tale of Two Copyrights: Literary Property in Revolutionary France and America, 64 Tul. L. Rev. 991 (1990).

[xvii] The period of protection was 14 years from the first publication and this could be extended if the owner was alive for a further 14 years,

[xviii] In fact, its full title is “An act for the encouragement of learning, by vesting the copies of printed books in the authors or purchasers of such copies, during the times therein mentioned”.

[xix] “The author is protected as an author, in his status as a creator, because a bond unites him to the object of his creation. In the French tradition, Parliament has repudiated the utilitarian concept of protecting works of authorship in order to stimulate literary and artistic activity” H. Desbois, Le Droit d’Auteur en France, 3 ed 1978, in Jane C. Ginsburg, A Tale of Two Copyrights: Literary Property in Revolutionary France and America, 64 TUL. L. REV. 991 (1990), p. 992.

[xx] O’Callaghan, Catherine. (2022). Can output produced autonomously by ai systems enjoy copyright protection, and should it? an analysis of the current legal position and the search for the way forward. Cornell International Law Journal, 55(4), p. 315. Civil law Author’s rights is regarded as author-oriented as opposed to common law copyright, which is regarded as society-oriented, although with the passage of time these differences have been diluted.

[xxi] All constitutional attempts prior to 1853 contained a reference to the protection of the rights or privileges of authors and inventors (see Provisional Regulations of 1817, the Constitution of 1819, the Constitution of 1826, the decrees of Bernardino Rivadavia of 1823, among others). The Constitution of 1853 stated in Article 17 that “Every author or inventor is the owner of his work, invention or discovery for the term granted by law”. The most recent constitutional reform included in Article 75, Section 19, a congressional mandate to “Enact laws that protect cultural identity and diversity, the free creation and circulation of authors’ works, artistic heritage, and cultural and audiovisual spaces”.

[xxii] For example, in 1994 the Government approved by decree No. 165/1994 a legal framework for the protection of Software and databases, to guarantee respect for intellectual property rights over works produced in this field.

[xxiii] In terms of international regulation, the first multilateral treaty was the Berne Convention for the Protection of Literary and Artistic Works, adopted in 1886 and revised several times, most recently amended in 1979 (See https://web.archive.org/web/20180523095521/http://www.wipo.int/treaties/en/text.jsp?file_id=283698). The Agreement on Trade-Related Aspects of Intellectual Property Rights (TRIPS Agreement), which came into effect in 1995, is to date the most comprehensive multilateral agreement on intellectual property. The TRIPS Agreement was negotiated at the end of the Uruguay Round of the General Agreement on Tariffs and Trade (GATT) between 1989 and 1990. During the Uruguay Round negotiations, it was acknowledged that the Berne Convention generally offered sufficient fundamental standards for copyright protection. As a result, the TRIPS Agreement stipulated compliance with these basic standards while also clarifying and introducing specific provisions to enhance international copyright protection.

[xxiv] It determines what the subject matter of protection is, who are the holders of the copyright, what are the related rights that the owner of the work can exercise by themselves or by third parties, among other aspects.

[xxv] Ascot Jockey Club Ltd v Simons. [1968] 64 WWR 411.

[xxvi] Under EU case law pre-dating Brexit the approach to assessing originality is to require work to be the “author’s own intellectual creation” to be protected by copyright, as stated by the ECJ’s decision in Infopaq International A/S v Danske Dagblades Forening (Case C-5/8) (“Infopaq”), concerning the interpretation of Directive 2001/29/EC on the harmonisation of certain aspects of copyright. This case centered on whether the temporary reproduction of 11-word extracts from copyrighted newspaper articles by Infopaq, a media monitoring and analysis business engaged in sending customers selected summarized articles from Danish daily newspapers and other periodicals by email, constituted a copyright infringement under EU law. The ECJ ruled that an 11-word extract of a protected work is a reproduction in part within the meaning of Article 2 of Directive 2001/29/EC, if the words reproduced are the expression of the intellectual creation of the author.

[xxvii] THJ Systems Limited & Anor v Daniel Sheridan & Anor [2023] EWCA Civ 1354

[xxviii] THJ Systems Limited & Anor v Daniel Sheridan & Anor [2023] EWCA Civ 1354, par. 16.

[xxix] Section 178, CDPA

Section 11(1), CDPA), and section 9(3), CPDA

[xxx] CPDA also contemplates exceptions to this general rule applicable to literary, dramatic, musical or artistic work or film where it is made by an employee in the course of his employment, where his employer is considered to be the first owner of any copyright in the work subject to any agreement to the contrary (Section 9(2), CPDA).

[xxxi] Some scholars suggest that the Courts may simply try to identify a human author for originality purposes even where a work is deemed to be a CGW, while others claim that S9(3) acts as an exception to the originality requirements in copyright law. See Copinger and Skone James on Copyright, Sweet & Maxwell, 18th ed, 2020 and Guadamuz, Andrés, Do Androids Dream of Electric Copyright? Comparative analysis of originality in artificial intelligence generated works, 2 Intell. Prop. Q. (2017) (updated June 2020 version).

[xxxii] Nova Productions Ltd v Mazooma Games Ltd [2007] EWCA Civ 219. This case involved a dispute over copyright infringement related to video game software. Nova Productions Ltd, the claimant, developed a video game, and Mazooma Games Ltd, the defendant, created a similar game. Nova Productions alleged that Mazooma Games copied elements of their game, including graphics and gameplay mechanics. The court held that while Mazooma’s game had similarities to Nova’s, the similarities between the two games were too general to amount to a substantial part of Nova’s game and that copyright protection does not extend to game rules, mechanics, or other unoriginal aspects, focusing on the idea-expression dichotomy in copyright law.

[xxxiii][xxxiii] Moreover, in the case THJ v. Sheridan, the court examined issues of authorship concerning “risk and price charts” presented in graphical displays[xxxiii]. Similarly as in Nova Production’s case, before the Court of Appeal, there was no dispute that, if the risk and price charts were original, then the creator of the software, Mr. Mitchell, was the author of them as he had designed the display making choices as to what to put where, in what order, what fonts and colours to use, among other things. These two cases suggest that a court is likely to deem the author of a CGW to be the computer programmer and not the program user.

[xxxiv] Cámara Nacional de Apelaciones en lo Civil, Sala D, 23/ 06/1976) ED 71-255. See also “(f)or an intellectual work to be protected, originality or individuality does not require thematic novelty, it is sufficient that it expresses the author’s own personality, that it bears the imprint of his or her personality”. Moreover, it has been said that “In order for there to be originality in the work, it is sufficient that there is a personal contribution of the spirit, of an intellectual nature (…) that reveals the imprint of his personality (…) It is, therefore, a question of fact, left to judicial assessment” Cámara Nacional de Apelaciones en lo Civil, Sala E 25/06/2004 (del voto del Sr. Juez Dupuis) «Santander de Santamaría, Cristina c/ López Gutiérrez, Benilde y otros».

[xxxv] Cámara Nacional de Apelaciones en lo Civil, Sala H, 5/6/2015 “M., M. c/ S., D. A.; s/Daños y perjuicios” elDial.com – AA9199.

[xxxvi] See Eduardo M. Favier Dubois, Handbook of Commercial Law, Ed. La Ley, 2016, Chapter 8 – Intellectual property and business. Section 3.3.

[xxxvii] The conclusions to these questions force doctrinarians to return to theoretical discussions on the foundations of copyright, and in general, the different positions reflect the discrepancies in this regard. Utilitarian theorists may present more robust arguments for justifying the subsistence of copyright in the context of AIGC, whereas naturalists may find it more challenging. This article does not intend to contribute to these discussions but rather to analyse whether such protection is possible under British and Argentine current standards.

[xxxviii] Jacopo Ciani, Learning from Monkeys: Authorship Issues Arising From Al Technology, in PROGRESS IN ARTIFICIAL INTELLIGENCE 275, 276 (Moura et al. eds., 2019).

[xxxix] European Parliament resolution of 20 October 2020 on intellectual property rights for the development of artificial intelligence technologies (2020/2015(INI)), par 14.

[xl] European Parliament resolution of 20 October 2020 on intellectual property rights for the development of artificial intelligence technologies (2020/2015(INI)), par 15.

[xli] O’Callaghan, Catherine. (2022). Can output produced autonomously by ai systems enjoy copyright protection, and should it? an analysis of the current legal position and the search for the way forward. Cornell International Law Journal, 55(4), p. 340.

[xlii] Nevertheless, for now, the applicable approach in the UK remains the requirement for a work to be the author’s own intellectual creation, as well as in Argentina.

[xliii] “It is plain that the degree of visual creativity which went into the R & P Charts was low. But that does not mean that there was no creativity at all. The consequence of the low degree of creativity is that the scope of protection conferred by copyright in the R & P Charts is correspondingly narrow so that only a close copy would infringe” THJ Systems Limited & Anor v Daniel Sheridan & Anor [2023] EWCA Civ 1354, par. 27

[xliv] In Argentina there is an express difference between author and owner, differentiating patrimonial rights from moral rights, proper to their continental roots. The latter are non-waivable and inalienable, i.e. their author cannot renounce them or transfer them to another person, unlike common law. https://www.herbertsmithfreehills.com/insights/2023-05/the-ip-in-ai-does-copyright-protect-ai-generated-works

[xlv] In Argentina, something peculiar happens, although our rules and regulations observe the provisions of the Berne Convention, Article 63 of Law 11.723 establishes: “Failure to register shall result in the suspension of the author’s rights until such time as the registration is made, and such rights shall be recovered in the very act of registration, for the corresponding term and conditions, without prejudice to the validity of the reproductions, editions, performances and any other publication made during the time the work was not registered.”

[xlvi] In Argentina, Article 17 of the National Constitution asserts that “Every author or inventor is the exclusive owner of his work, invention, or discovery for the term granted by law.” Law 11.723, which governs intellectual property, uses “author” to refer specifically to human beings. This is supported by Article 4, which identifies “the author of the work” and “their heirs or successors” as holders of intellectual property rights, and Article 5, which states that “Intellectual property over their works belongs to the authors during their lifetime.” These references to heirs and the author’s lifetime therefore clearly indicate that the term “author” is intended to apply only to humans.

[xlvii] In Argentina, where copyright law traditionally places the main emphasis on human authorship, a sui generis system would require substantial reconciliation and modification of these guidelines/principles. On the other hand, in the UK, where the legal framework is more flexible but still rooted in human creativity, the introduction of sui generis rights may be more easily accommodated, because there is no moral element from the point of view of authorship that prevents this. It is also important to remember that both jurisdictions would have to consider how this new system aligns with international obligations, in particular under international treaties to which they have acceded, such as the Berne Convention. This delicate balance highlights the need for a nuanced approach that respects local legal traditions while taking into account the global nature of AI technology. Consideration has even been given to creating figures such as AI as an author in academia, see an interesting paper below: Annemarie Bridy, Coding Creativity: Copyright and the Artificially Intelligent Author, 2012 STAN. TECH. L. REV. 5 http://stlr.stanford.edu/pdf/bridy-coding-creativity.pdf

[xlviii] The United Kingdom is among the few jurisdictions that include specific statutory provisions within its copyright legislation addressing the authorship of computer-generated works. Notably, the term of protection for such works is limited to 50 years from the end of the year in which the work was made, contrasting with the 70-year term post-mortem auctoris applicable to human-generated literary or artistic works.

[xlix] Generative AI tools are new and best practices and norms for commercial contract terms are still developing. Indeed, the UK IPO is currently preparing a code of practice on accessing copyrighted materials, and those who subscribe to it “can expect to be able to have a reasonable licence offered by a rights holder in return”. Please refer to The government’s code of practice on copyright and AI, UK Government. Link: https://www.gov.uk/guidance/the-governments-code-of-practice-on-copyright-and-ai For instance, OpenAI grants all the ownership rights to the user, please see the T&Cs for ChatGPT, DALL·E, and OpenAI’s other services for individuals from November 14, 2023 onwards. For reference please see as follows: https://openai.com/policies/terms-of-use/ By the same token, Gemini (Google) allows a non-assignable, non-exclusive, worldwide, and royalty-free limited licence to use the software and the content that derives of the use of this, please see as follows: https://www.gemini.com/legal/user-agreement#section-general-use

[l] Taylor Wessing, Using and training generative AI tools – IP ownership and infringement issues, link: https://www.taylorwessing.com/en/interface/2023/ai—are-we-getting-the-balance-between-regulation-and-innovation-right/using-and-training-generative-ai-tools—ip-ownership-and-infringement-issues

[li] Ibid.

[lii] Concerns regarding data protection issues have arisen in both jurisdictions, for instance in Argentina, see: La Ley, Los retos legales de la inteligencia artificial en ChatGPT, Florencia Rosati and Mariana Lamarca Vidal, link: https://beccarvarela.com/wp-content/uploads/2023/05/retos-legales-chat-gpt_rosati_lamarca.pdf

[liii] In its Terms of Use published on 14 March 2023, OpenAI has sought to address this issue by including a clause that states: “Other users may also ask similar questions and receive the same response. Responses that are requested by and generated for other users are not considered your Content.” This suggests that OpenAI recognises the challenges posed by duplicate outputs and competing claims by multiple users. Generative AI – the copyright issues, Simmons & Simmons, link: https://www.simmons-simmons.com/en/publications/clgxkqd5z000utrj8zuuc5cms/generative-ai-the-copyright-issues

[liv] Consumer protection in Argentina is primarily governed by Article 42 of the National Constitution, the Argentine Civil and Commercial Code (Articles 1092–1122), and Consumer Protection Law No. 24,240. Additional regulations include Regulatory Decree No. 1798/1994 and Decree No. 274/2019 on Unfair Trade and Unfair Competition. Relevant resolutions from national, provincial, and municipal authorities, along with Mercosur Resolutions incorporated into Argentine law, also play a role. In the UK, statutory pieces such as Consumer Protection from Unfair Trading Regulations 2008, CDPA, or the Data Protection Act (2018) may affect this point.

[lv] The UK Government has said the following regarding false attribution: “We do not think that false attribution is a substantial issue at present. There are already provisions in law that may be relied upon if works are being falsely attributed to humans. For example, the Fraud Act 2006 includes provisions to penalise people who make false representations for gain. We think this is sufficient to address any existing or near-future issues relating to false attribution and AI. But we would welcome further views on this issue.” Link: https://www.gov.uk/government/consultations/artificial-intelligence-and-ip-copyright-and-patents/artificial-intelligence-and-intellectual-property-copyright-and-patents

[lvi] The UK House of Lords Digital and Communications Committee issued a report on LLM and Generative AI in February 2024 (see our blog post here), calling on the UK Government to support copyright holders, stating that the Government “cannot stand idly by” while LLM developers exploit rights holders’ works. HOUSE OF LORDS, Large language models and generative AI, link: https://publications.parliament.uk/pa/ld5804/ldselect/ldcomm/54/54.pdf Data protection issues surrounding the training of generative AI tools have recently come to the forefront. Last year, stock-image supplier Getty Images initiated proceedings against Stability AI Ltd., the provider of the popular AI image-generator Stable Diffusion, in the English High Court. Correspondingly, Getty Images has filed a claim in the Delaware courts against Stability AI, Inc., the parent company of Stability AI Ltd. Similar cases have also been brought in the California courts against Midjourney, DeviantArt, and GitHub. Link: https://www.cliffordchance.com/insights/resources/blogs/talking-tech/en/articles/2023/04/the-intellectual-property-and-data-protection-implications-of-tr.html

[lvii] In 2023, the United Kingdom’s Information Commissioner’s Office and data protection authorities from Canada, Australia, Hong Kong, Mexico, Switzerland, Norway, New Zealand, Colombia, Jersey, Morocco, and Argentina have released a joint statement on data scraping and its impact on data privacy. Please see the joint statement on data scraping and the protection of privacy (24 August 2023), link: https://ico.org.uk/media/about-the-ico/documents/4026232/joint-statement-data-scraping-202308.pdf Failure to comply with these provisions can lead to legal repercussions and sanctions by the Access to Public Information Agency, the Argentine data protection regulator.